On Writing – Part III: To Be Brief or Not to Be

When I first started out, I read the "little book" by Strunk and White. I figured that it would give me a quick intro to grammar. It was awesome. The examples were beautiful, and I had the impression that two grouchy professors were telling me, “This is the way English is written. Now, shut up and do it right.”

Their mantra was: "Keep it short, stupid."

So I wrote neat little sentences. Didn't work. The editor said, "Your stuff is too choppy; fix it." So I hooked the little sentences together with a semicolon. Didn't work. The editor said, "Gotcha, you just hooked your little sentences together with some punctuation. I'm onto you. Fix it."

Then it got worse. The editor said, "Only Hemingway can get away with short sentences, and you're definitely not Hemingway."

So, what does "keep it short," really mean?

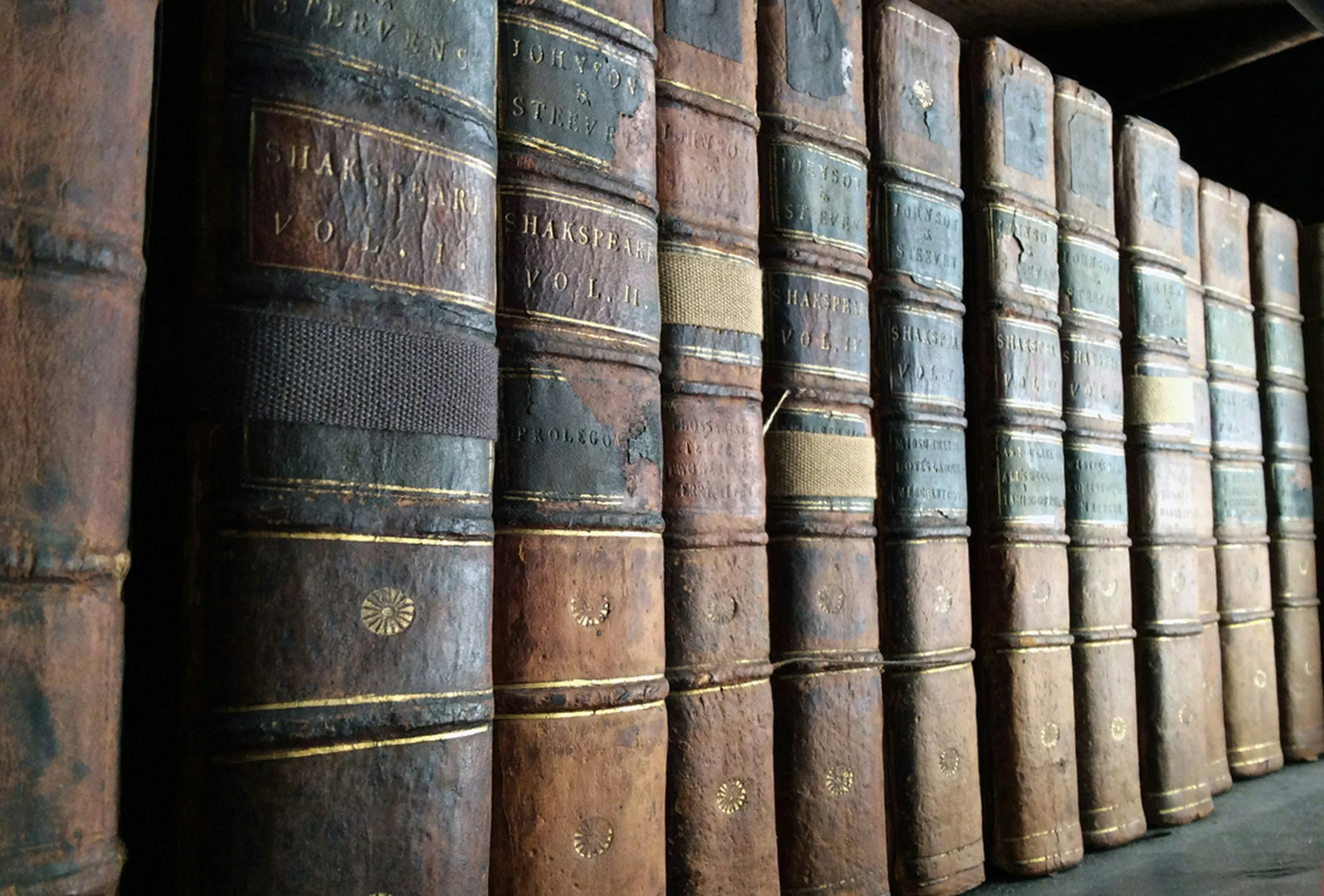

Reedsy instructors said to analyze writing styles, and maybe you might learn something. The trouble was that every time I did that, I got discouraged. Anyway, take a look at this sentence. It's from Hamlet, and I think everybody agrees that Will Shakespeare knew what he was doing.

To be or not to be, that is the question: Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, or to take arms against a sea of troubles, and by opposing end them.

Now that is one long sentence, and there's a lot of commas, but between those commas, he uses very few words, so you know exactly what he means. I think of it as a roller coaster ride through glorious prose.

So, what did that have to do with me? If I was not Hemingway, I most certainly was not Shakespeare.

For me, "keep it short" really means expressing thoughts clearly and concisely, without extra words that muddle the meaning. Doesn't matter how long the sentence is, as long as the reader can comprehend it.

OK, but I should still watch the long sentences and not pull a Charles Dickens:

It was the best of times; it was the worst of times, ...

Everybody knows that one, but the sentence runs on for a whole page, and by the end it's like, "What happened?" C'mon Chuck, help us out with a couple of periods—maybe even a paragraph.

Some writers—Lawrence Durrell, for example—can get with florid prose: The Alexandria Quartet is wonderfully dense, but it wouldn't be the same without the ornate writing style.

In other words, I should be reasonable about the length. For me, that wasn't a problem; I couldn't think of a long sentence to save my life.

So I tried leaning back, aiming for the bleachers, and letting the words flow as they were meant to do.

And you know what? It was a lot of fun.

Any thoughts?