Will the Real Cleopatra Please Stand Up?: Part I

My second book was about the search for Cleopatra’s tomb. Let me share some thoughts.

Cleopatra: the very name evokes imagery.

Her full name was Cleopatra VII Thea Philopater. Cleopatra means “glory of the father” or “father-loving goddess,” depending on the translation.

Like everyone else, I watched the 1963 film Cleopatra, starring Elizabeth Taylor as the great queen. I was riveted by the image of a gorgeous woman being towed into the Roman forum on a giant sphinx. The sets were gigantic, and many were destroyed in the Italian rain. I saw a small piece of one in a Monterey antique store. It was an Egyptian Pharoah’s head. I don’t know where the store owners got it, but it was bigger than my living room wall.

I stared at it. What drove Hollywood to produce such an epic? It was hugely over budget from the beginning. Did the directors hope to contain Cleopatra on a roll of film? I don’t know, but what I can conclude is that her mystique captured these otherwise hardboiled, no-nonsense men of Hollywood, just as she captured Caesar himself.

Caesar, the man who declared himself emperor of the known world, was putty in the hands of a twenty-two-year-old girl. He was about fifty-five at the time, and the foremost lecher in the Roman world. He didn’t stand a chance. French orientalist painter Jean-Leon Gerome portrayed the moment when she arose from the carpet to confront a dumbfounded Caesar at his desk. Imagination, of course, but she did get into Caesar’s heavily guarded villa and the rest is history.

But what does this have to do with the real Cleopatra?

In my book, young and quirky detectives Flinders and Pettigrew are hired to search for her tomb. Everybody who is anybody searches for her tomb. That is because some historical accounts say she killed herself in it. The legend is that she was bitten by an asp and died in her tomb along with her handmaidens, and then was buried there by Roman emperor Octavian.

A beautiful and poignant ending for a great queen.

Consider Shakespeare’s lines: “Where art thou, death? Come hither, come! Come, come, and take a queen.”

Shakespeare wrote Antony and Cleopatra in the 17th century, following the writings of the Greek historian Plutarch, who wrote around 100 CE—serving as one of the asp-bite legend sources about two hundred years after Cleopatra’s death. Since then, just about every famous actress in the world has had a go at portraying the great queen: Sarah Bernhardt, Theda Berra, Claudette Colbert, Elizabeth Taylor, and Adele James all tried their hand.

But there is a problem with the asp bite story.

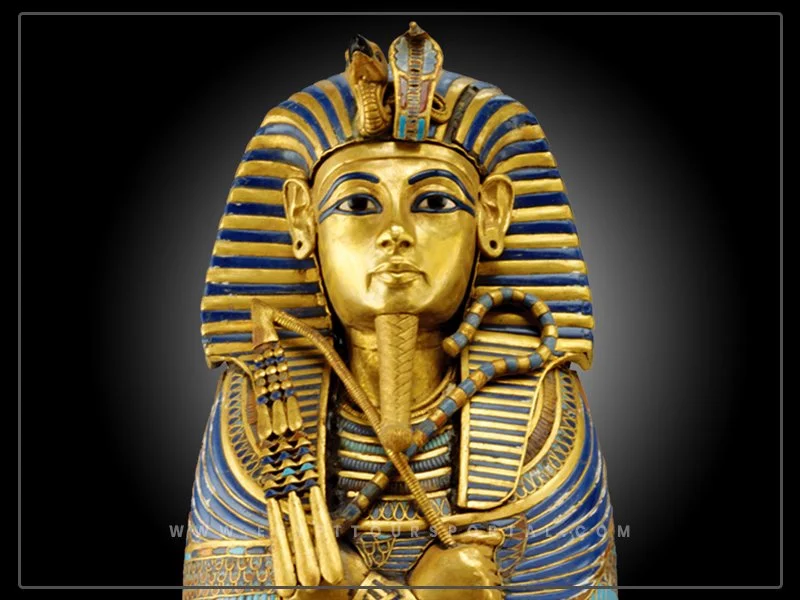

The asp was a symbol of royalty in ancient Egypt; the Egyptian cobra is a species of asp. Photographs of Egyptian pharaohs show a snake rearing to strike on their headdresses. Death by asp bite was a form of execution in Cleopatra’s time: It was reserved for individuals thought to be deserving of a dignified death.

But did she commit suicide by asp bite? Maybe and maybe not.

The Egyptian cobra is a large snake around five feet long—not at all like the small viper in all the portraits. Furthermore, its bite doesn’t always kill, and when it does, its venom takes about an hour to work. Death is by asphyxiation. When Cleopatra had herself bitten, she sent a note to Octavian who had a nearby villa. His men rushed to the mausoleum and found her dead. With an asp bite, the timeline doesn’t work.

Some ancient accounts indicate that Cleopatra injected herself with a sharp instrument. There are stories that she experimented with various poisons on condemned people well in advance of her death and concluded that death by asp bite was the least painful. Poison was her weapon of choice, and she no doubt was an expert in its use. Apparently, she carried cobra venom around just in case she was captured by enemies. It was probably not straight cobra venom, which would be too slow, but a mixture of poisons. In 2010, a German toxicologist argued that Cleopatra may have used such a mixture and died a pain-free death.

Nevertheless, the asp bite narrative makes perfect symbolic sense. The great queen kills herself to avoid being dragged through Rome in disgrace and then put to a horrible death. And she does so in a royal manner. As legend, the precise manner of her death does not make any difference. And the story connects Cleopatra’s death with the Isis myth which she exploited during her lifetime. Cleopatra identified herself with Isis; she even dressed as her.

Isis was the Egyptian goddess embodying divine feminine energy. Ancient Egyptian mythology says that Isis saved Ra from a cobra bite. By Cleopatra’s time, the Isis serpent motif was ingrained in pharaonic culture. Cleopatra’s death by snake bite thus takes on mythological proportions.

What happened may never be known, but the fact that there is still a debate two millennia later is testimony to Cleopatra’s enduring mystique. The men of Hollywood were clearly moved by it, and for that matter, so is everybody else.

Any comments?