Will the Real Cleopatra Please Stand Up?: Part II

So what did Cleopatra actually look like?

The current generation thinks she looked like either Elizabeth Taylor or Adele James. Earlier generations favored Claudette Colbert, Theda Bara, or Sarah Bernhardt. But are any of those depictions really true? Probably not. The myth of this beautiful and tragic queen has overwhelmed the scant archeological evidence.

Consider the problem: There is no photographic evidence or portraiture. All we have are statues, coins, and maybe some historically derived eyewitness accounts—and even these offer contradictory images.

Take the statues, which are of two sorts: pharaonic and Greek. The pharaonic images present her as a pharaoh very much like other pharaohs, consistent with the prevailing official artistic conventions. No surprise here: She was a pharaoh and would expect to be portrayed as such. The Greek versions portray a Greek woman with a long nose. Some have argued that she is clearly pictured as a blonde woman. They are examples of late Hellenistic realism. Again, no surprise: The Ptolemies were a fanatically Greek dynasty and would be expected to utilize Greek imagery in portraying themselves.

Here’s the catch.

Ancient statues and monuments were designed as political communication, and they didn’t just pop up. Perish the idea of some artisan chipping away in a hovel. Cleopatra’s statues were aimed at specific audiences, and subject to her artistic approval. The Greek versions fit nicely into one of the Ptolemies’ palaces already filled with Greek and Egyptian art. Take a look at the underwater pictures of her sunken palace, and you will see what I mean. The pharaonic statues loomed over public places to remind passersby of the pharaoh’s majesty, and they all took months, even years to create. My guess is that they were presented to a committee and budgeted just like any other royal expenditure.

The coins present another conundrum.

They are struck with an almost Roman image: a heavy-braided figure with a thick neck and pronounced nose and chin—a caricature reminiscent of the “Wicked Witch of the West,” almost more masculine then feminine. The image is more suited to a later Roman emperor than the ancient world’s most beautiful woman, but coinage is a public relations opportunity. For sovereigns, power, majesty, and even menace count; “prettiness” does not.

So, can we ever know what she looked like?

Probably not.

There are some hints, however.

Plutarch offers this famous description: “Her beauty was not exceptional enough to instantly affect those who saw her, but she had a charming way of conversing, and an invigorating presence. Her sweet voice was as well-modulated as a lyre, and she could speak whichever language she pleased.” The problem is that Plutarch was writing a hundred years or so after Cleopatra’s death, and he is describing a woman who regularly poisoned people.

For what it’s worth, then, Cleopatra was a charming woman—when she wanted to be, that is. By all accounts, she had a ferocious temper.

But in the absence of any definitive evidence, writers, scholars, and politicians filled in their own images, and those images changed with the times. Medieval theologians viewed her (unfavorably) through Christian lenses. Baroque artists portrayed her lying on a fainting couch, very much in the manner they portrayed other famous ladies, with one difference: The other ladies are pretty much buttoned up, but Cleopatra is bare breasted, a tribute to male fantasy rather than archeological accuracy. There is no reason to expect that she dressed differently from the conventions of her time. Remember, she was the head of state, and no doubt expected to uphold conventions.

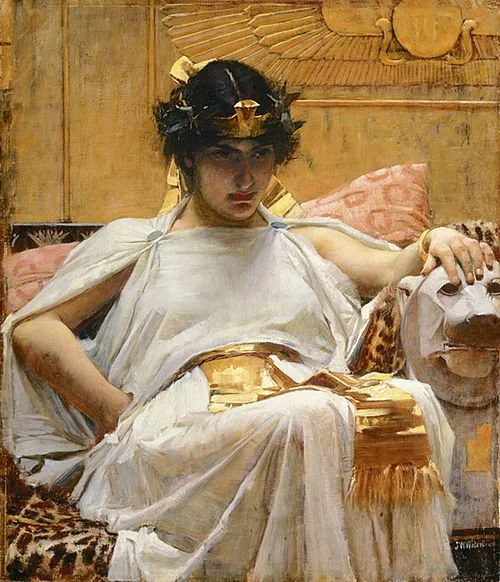

If you want my thoughts, take a look this portrait I used on the cover of The Cleopatra Caper, painted by John Waterhouse in 1888. The portrait revolutionized the way Cleopatra has been presented from then on.

Waterhouse clearly captures her brooding sense of power. This is a ruler that had two seventy-ton obelisks towed across Egypt because she wanted them in Alexandria. This is a ruler who has seen just about everything. This is a ruler who will not put up with any nonsense. She does not look like someone you would care to cross, and she definitely does not have the Liz Taylor look.

Well then, if we don’t have any descriptions, can we guess what Cleopatra thought of herself?

Maybe.

Some Roman writers suggest that she was unduly flamboyant. She did like to array herself in finery, but that could just be part of the job of being pharaoh. She took baths in goat milk and honey, and she had a passion for pearls. There is a famous story that she once took off a pearl earring, dissolved the pearl in wine, and then drank it to impress Mark Anthony by demonstrating her disdain for mundane objects. Probably not true, but pretty cool anyway. Anthony, who no doubt had a good idea of his wife’s self-image, built the famous baths in Alexandria, a testimony in stone to her delight in bathing.

Finery, pearls, and bathing in goat milk all suggest a woman who was preoccupied with her beauty, but in the absence of anything concrete, imaginations are free to roam. Viewers project their own thoughts onto her image, and a lot of those thoughts are just pure propaganda.

After all, we are talking about a legend.

I think the mystique that surrounds Cleopatra and what she looked like creates a sense of wonderment. Let me close with an excerpt from Cleopatra that I hope captures some of this wonderment.

The young detective, Flinders, wanders through the baths until he comes to a dead end. He notices that an opening seems to have been plastered over in ancient times.

He breaks through:

“Flinders stepped through the opening and into the past.

“Light blinded him. Flinders’ eyes had become adjusted to the gloom of the outer chambers and were now dazzled by sunlight. When his vision cleared, Flinders saw that he was in a circular room. At its center was a pool filled with still water. Surrounding the pool were fluted columns; marble benches were interspersed between the columns. A circular opening let in bright sunlight, its round cornice resting on the column’s capitals. Some of the columns were circled by vines with red flowers. Birds chattered in the dark recesses. A flight of marble steps faded into the pool’s cloudy green depths, and a slight rose scent permeated the chamber.

“He sat on one of the benches; the marble was warm. Warm from the sun or from some presence?

“He looked at the open cupola. A small grey bird with white wings sat on its edge. ‘Did your ancestors sit on this edge and watch Cleopatra bathing? Do you also have some half-remembered ancestral memory from your forebearers?’

“This must be where she bathed. The sudden wonder of it all overwhelmed him: Cleopatra was here, and she might have just left through one of those doors. He stared at the opening hoping for the fleeting glimpse of a white robe, or a golden diadem. The thought overwhelmed him. I am walking on the very marble tiles that Cleopatra walked; I am sitting on a bench where she might have rested. Two thousand years of time have just disappeared…“

And there you have it.